About Giant Sea Bass

Species overview

Giant sea bass (Stereolepis gigas), known as mero gigante in Mexico, are the largest resident bony fishes in California. The biggest giant sea bass ever recorded was 2.26 meters (7.4 feet) long and weighed 256 kilograms (563.5 pounds). They are long-lived, reaching at least 72-75 years, and are slow to mature, reproducing for the first time at 13-15 years old.

Young juveniles, which are typically less than 20 centimeters (8 inches) long, are bright red or orange with dark spots. Adults are gray or brown with black spots. Individuals can temporarily change (flash) the color and brightness of their skin and spots.

Natural History

Feeding Habits

Giant sea bass are apex predators in kelp forest ecosystems and feed on fishes, crustaceans, squid, small sharks, and rays. Generally slow-moving, they suck prey into their mouths by abruptly opening their jaws and creating a strong vacuum.

Habitats

Giant sea bass spawn between the months of May and September. During this time, they are typically seen on nearshore rocky reefs and kelp beds. Giant sea bass eggs and recently hatched larvae will float around as plankton before making their way down to the seafloor between October and December. Adults have been observed in depths ranging from 5-46 meters (18-150 feet), but are believed to move deeper during the fall and winter. However, scientists and managers lack information about where they move to and what habitats they use during this time.

Distribution

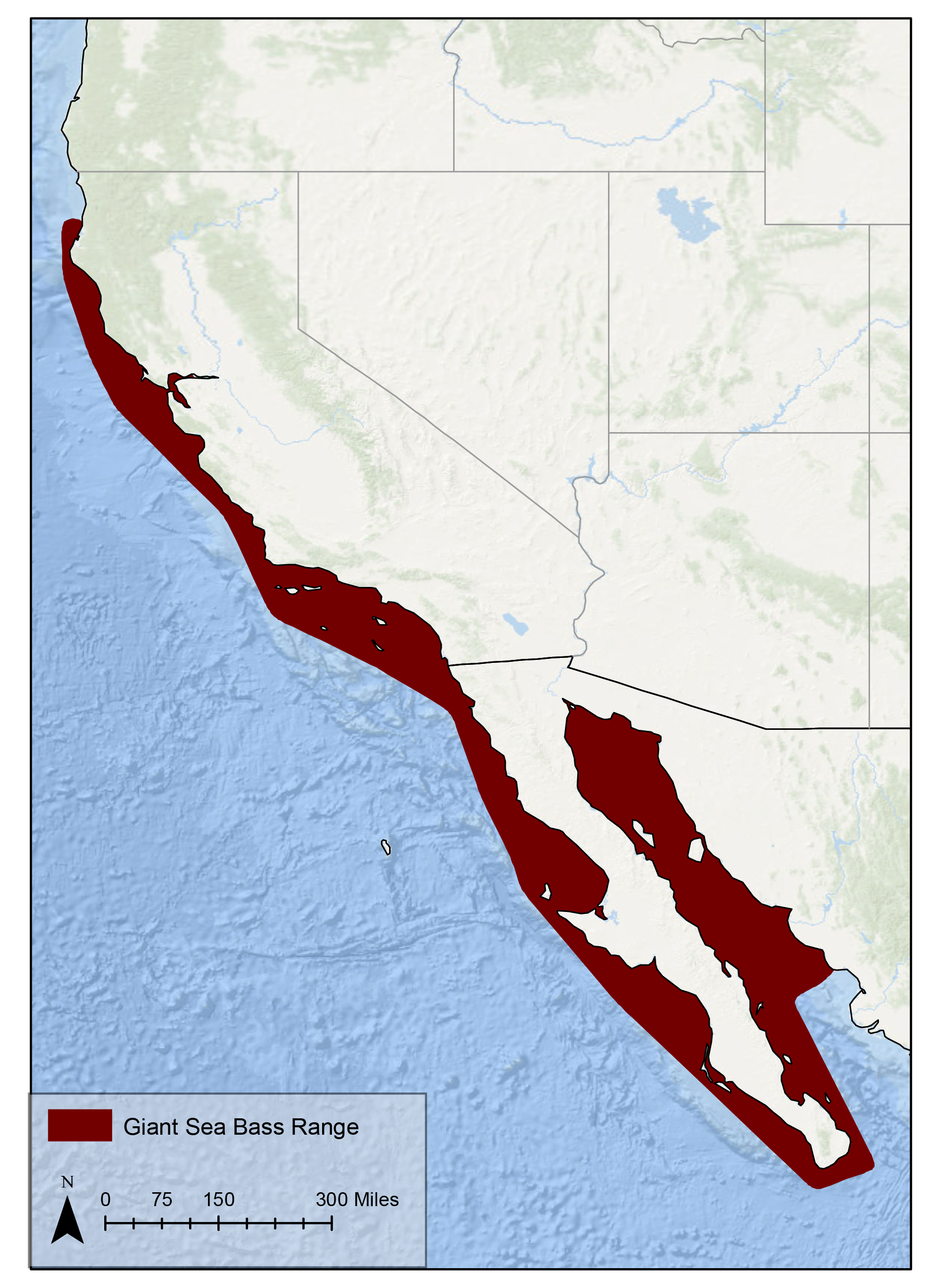

The range of giant sea bass extends along the west coast from Humboldt Bay (Northern California) to Oaxaca (Southwestern Mexico). Within California, they are primarily seen around and to the south of the Northern Channel Islands. In Mexico, they are mostly found on the Pacific coast of Baja California and the Sea of Cortez.

Population and Conservation

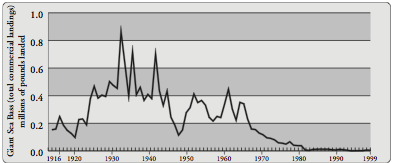

Giant sea bass were once a common and valuable species in fish markets. Commercial fishing for them began in the 1800s. Catch peaked in 1932 for commercial fisheries in both California and Mexico. Recreational fishing of giant sea bass increased after the commercial peak, and recreational catches peaked in 1963 in California and 1973 in Mexico. The development of recreational fisheries that targeted giant sea bass spawning aggregations contributed to a quick collapse of the population. Giant sea bass numbers continued to steadily decline until 1981. That year California passed a law restricting targeted recreational and commercial fishing of giant sea bass, with the exception of one incidentally caught fish per fishing trip in the commercial gillnet and trammel net fisheries. Today, approximately 97 giant sea bass are landed annually and sold in California in these commercial fisheries.

Based on the severity of these declines, since 1996 giant sea bass have been classified as a Critically Endangered species on the red list of the International Union for Conservation of Nature. Recent research suggests that giant sea bass populations might be increasing, but their numbers have not recovered to levels anywhere near those recorded during the early 1900s.

References

Allen LG, Andrews AH (2012). Bomb radiocarbon dating and estimated longevity of Giant Sea Bass (Stereolepis gigas).

Bulletin, Southern California Academy of Sciences 111:1-14. doi: 10.3160/0038-3872-111.1.1

Domeier, ML (2001). Giant sea bass. California's living marine resources: a status report.

Calif Fish Game, Sacramento, 209-211.

Gaffney PM, Rupnow J, Domeier ML (2007). Genetic similarity of disjunct populations of the giant sea bass Stereolepis gigas.

Journal of Fish Biology 70:111-124. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8649.2007.01393.x

House, Parker H., Brian LF Clark, and Larry G. Allen (2016). The return of the king of the kelp forest: distribution, abundance, and biomass of giant sea bass (Stereolepis gigas) off Santa Catalina Island, California, 2014-2015.

Bulletin, Southern California Academy of Sciences 115.1: 1-14.

Pondella DJ, Allen LG (2008). The decline and recovery of four predatory fishes from the Southern California Bight. Marine Biology 154:307-313.